The one thing you never want to see in your web pages—whether on your blog, your wiki, or your own website—are pages with nothing but a wall of text: no links, no headlines, no images.

People like to scan and skim on the web. This is no surprise. Readers have skimmed and scanned ever since newspapers started cramming their pages with information centuries ago. We are hunters and gatherers searching for information, as web content strategist Ginny Redish likes to say in her book, Letting Go of the Words. We don’t read, we hunt. If we do not think your page offers the information we want, we move on. Quickly.

Consider the times you have used a search engine to look for information on a particular topic. Type in your keywords. Google shows you 150,234 results. How do you choose what to read? The page title that is displayed to you in the search engine results influences you on whether or not to visit that web page. And then once you visit a web page from your search results, you will often skim the headings (when available) to find what you need. If the headings aren’t yielding fruitful indications that you are in the right place, you may leave and try another search result—even though the information you seek was actually there.

Or think about the times you have jumped on your favorite news site (e.g., CNN, ESPN, Wired, etc.). Much like when reading newspapers, the first thing most readers do is skim the headlines looking for something to catch their interest. Readers do the same thing when they visit a blog that they haven’t been to before. As Copyblogger points out at the beginning of his tutorial about writing headlines for the web,

Your headline is the first, and perhaps only, impression you make on a prospective reader. Without a compelling promise that turns a browser into a reader, the rest of your words may as well not even exist. . . . On average, 8 out of 10 people will read headline copy, but only 2 out of 10 will read the rest.

Editors of professional news publications and serious bloggers know this, and they typically spend significant amounts of time coming up with the right headline to attract readers. Whether you are keeping your own weblog, creating an information page for a client, working on a wiki page, or building a personal portfolio website, you’ll need to take some time, too, to create page titles, headings, and subheaders that invite your reader to explore and understand the content you have created.

Every Page Needs a Title

A recent Google search for the phrase “Untitled Document” yielded 47 million hits. What’s with that? Are untitled documents the latest Internet meme? Are they a viral YouTube sensation?

Nothing so exciting. When you encounter one of those 45 million web pages that has “Untitled Document” in a tab or a window, what you see is a lost opportunity: you are looking at a Web page with no page title.

Page titles also appear in places that are totally apart from the actual web page you have written. For example, your page title appears in representations of your open page in the taskbar or dock; it appears in history and bookmark lists, and it is used in search results and RSS feeds. Because a page title has a life separate from the page it represents, you should write page titles that provide both context and topic so that the page title can stand alone. What does a page title like “home” or “intro” tell you about a web page when viewed in an RSS feed? What about “Blog #1 or “Please Read”? Do you really have so much free time on your hands that you’re willing to click on one of these?

Many blogging platforms, such as WordPress, automatically add the name of a site to a page title, making your life easier, but if you are creating web pages from scratch or if you are working with blogging software that is not as page-title friendly as WordPress, be sure to include in your page titles both your major headline and the name of your site.

Subheaders and Lists

In addition to page titles, you also want to break up your text with subheaders. Generally speaking, pages you write for the web won’t look like the papers you turn in to professors. Nothing says “move on without reading” to web users like walls of unbroken text. Ginny Redish recommends that you think of your subheaders as a conversation that you are having with your user. People come to your pages with questions. Use your subheaders to answer those questions.

Here is a page from the website of the English Department at Illinois State University about English minors with all of the subheaders and other formatting removed:

Minors are a combination of courses designed to provide a cohesive introduction to an area of study beyond the student’s major. The English Department offers four minors: English Studies, English Education, Writing, and Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL). English faculty and English courses are also included in a variety of University-wide minors. Minor in English: The minor in English is a good choice if you want a minor with a variety of English courses. Learn more about the minor in English. Minor in English Education: The minor in English Education is an option for students in other Secondary Education programs who wish to be endorsed in the Language Arts. By completing the minor, you will be certified to teach Language Arts in addition to your major area. Learn more about the minor in English Education. TESOL: The TESOL minor is most often taken by students who are seeking an endorsement in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL). Learn more about the minor in TESOL. Writing: The writing minor is taken by students in a variety of majors. Students in the minor can specialize in creative writing, technical writing, or rhetoric and composition. Learn more about the minor in Writing. University-wide Minors Students selecting a University-wide, interdisciplinary minor can take advantage of the many exciting resources of a large university community. Learn more about University-wide minors.

How much time would you be willing to invest searching for information about a minor that interested you? Figure 12 shows a part of the page as it is actually rendered on the department’s website.

Notice that on this page, you can easily find information about the various minors.

Figure 1. Example from English Minors at Illinois State University of content organized into short paragraphs and subheaders.

Don’t Forget Lists

Lists, both numbered and bulleted lists, are another form of subheaders in that they make the underlying structure of your content visible to your readers. A good list can make clear the steps in a process, the advantages of an option, or the requirements of a program. Here is another bit of text from the Illinois State English Department Website about the requirements for an internship with all of the list formatting removed:

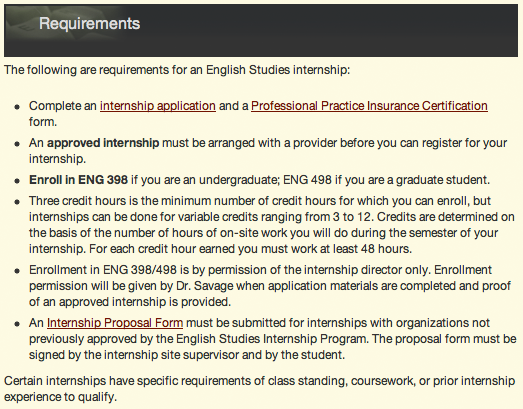

The following are requirements for an English Studies internship: Complete an internship application and a Professional Practice Insurance Certification form. An approved internship must be arranged with a provider before you can register for your internship. Enroll in ENG 398 if you are an undergraduate; ENG 498 if you are a graduate student. Three credit hours is the minimum number of credit hours for which you can enroll, but internships can be done for variable credits ranging from 3 to 12. Credits are determined on the basis of the number of hours of on-site work you will do during the semester of your internship. For each credit hour earned you must work at least 48 hours. Enrollment in ENG 398/498 is by permission of the internship director only. Enrollment permission will be given by Dr. Savage when application materials are completed and proof of an approved internship is provided. An Internship Proposal Form must be submitted for internships with organizations not previously approved by the English Studies Internship Program. The proposal form must be signed by the internship site supervisor and by the student. Certain internships have specific requirements of class standing, coursework, or prior internship experience to qualify.

Does it make your head hurt to work through this list? Figure 13 shows the same information organized in a list as it appears on the website:

Figure 2. Example from Internship Qualifications and Requirements of content organized into a list.

Notice how it is much easier to see what you need to do to secure an internship when the steps are organized in a list.

You may also have noticed that in these negative examples, there weren’t any paragraph breaks, and instead, the information was presented as one long paragraph. In both examples, putting each new topic in its own paragraph would have made the text much more readable.

Keep your paragraphs short when you write on the web to help your readers. Well-written, short paragraphs have much the same impact as subheaders and lists: they break your text into visible chunks that help the reader find the information he or she is looking for quickly.

Can I Use Catchy Titles and Headings?

Catchy titles and headings can be helpful in some writing contexts, such as on news publications or a blog, where the goal is to attract a loyal following of readers. They might not be such a good choice for a business website or other more formal professional writing situations, depending on the overall tone that is being set for the site.

Think about the purpose of your text. Are you trying to help users locate specific bits of information or answer specific questions they may have? If so, then simple direct headlines and subheaders are probably a better choice. But if you are trying to encourage web users to stop and read your content, then a catchy title can be a good idea, especially if it leads to catchy, engaging writing.

If you choose to use catchy titles for your web pages, beware of making them too mysterious. They should at least hint at at the focus of the content. Otherwise, readers who are actually interested in the specific focus of the page may not realize what it’s about.

Don’t Forget about Your Other Audience: The Search Engine

There’s another “reader” of your website that’s as important as your human readers: Search engines. How often do you use a search engine to find new content? Most of use them all the time.

When you use a search engine, you aren’t actually searching the Web; you are searching a database of website content information selected and maintained by the search engine provider. Search engine companies employ computer programs known as “bots” to surf the Web and gather that information. They then employ a ranking algorithm that uses various factors to determine where (and if) a web page should show up in a search for specific keywords.

The good news is that generally the advice for writing good titles and headings for human readers will work well for search engines. Informative titles and headings help search engines to index your content. Like your readers, search engines predict that the titles and headings reveal the main content of your web page, and they use the keywords from within them in indexing your content: better titles and headings equals better search engine ranking results for your web pages.

Incidentally, the practice of “writing” for search engines is known as search engine optimization (SEO). If you want to learn more strategies and tips for improving the search engine ranking of your own or your employer’s website, check out SEOmoz’s tutorial The Beginner’s Guide to SEO.

Use Your Platform’s Heading Styles, and Life Will Be Good

Once you have come up with a good title for your writing and subheadings to use within it, you’ll need to enter them on your site.

When using a tool like WordPress, you’ll likely be creating your text using a visual editor which gives you formatting controls. Beware the temptation to style your headings using bold, italics, and font size changes. Your website likely already has styling set for different headings as part of the overall site theme; you just have to “tag” the heading by applying heading styles: H1, H2, H3, etc.

Why tag your headers? When you tag your headlines and subheaders, you are letting the web do the work for you. If you switch to a new theme for your website, all of your Heading 3 headlines will automatically change to the new Heading 3 style used in your theme, but any headlines you have styled by hand will have to be changed by hand: each and everyone, over and over and over again.

Adapted from Writing Spaces Web Writing Style Guide, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) License.